National Security

A sword and scabbard from a bas-relief at Persepolis, ca. 500 B.C. During the 1970s, imperial Iran developed one of the most impressive military forces in the Middle East, and it used those forces to assume a security role in the Persian Gulf after the British military withdrawal in 1971. The defense of the strategic Strait of Hormuz preoccupied the shah, as it did the other conservative monarchs in the area. Freedom of navigation in the Gulf was important for international shipping, and the shah was perceived, at least in certain quarters, as the undeclared "policeman of the West in the Gulf." When independent observers concluded that Iran's military buildup exceeded its defensive needs, the shah declared that his responsibilities extended beyond Iran and included the protection of the Gulf. Increasingly, the military played a pivotal role in promoting this policy and, in doing so, gained a privileged position in society. Under the Nixon Doctrine of 1969, according to which aiding local armed forces was considered preferable to direct United States military intervention, Washington played an important part in upgrading the Iranian military forces. The United States supplied Iran with sophisticated hardware and sent thousands of military advisers and technicians to help Iran absorb the technology. By 1979 the United States military presence in Iran had drawn the wrath of Iranians. Ayatollah Sayyid Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini specifically identified the shah's pro-American policies as detrimental to Iranian interests and called on his supporters to oppose the United States presence. He cited special legal privileges granted United States personnel in Iran as an example of the shah's excessive identification of Iran's interests with those of Washington. Following the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the armed forces underwent fundamental changes. The revolutionary government purged high-ranking officials as well as many mid-ranking officers identified with the Pahlavi regime and created a loyal military force, the Pasdaran (Pasdaran-e Enghelab-e Islami, or Islamic Revolutionary

Guard Corps, or Revolutionary Guards), whose purpose was to defend

the Revolution. When the Iran-Iraq War began, however, the revolutionary government had

to acknowledge its need for the professional services of many of the

purged officers to lead the armed forces in defending the country against Iraq. The army was

unexpectedly successful in the war, even though, as of 1987, the regular

armed forces continued to be regarded with considerable suspicion. Within the Iranian military there was competition between the regular and irregular armed forces. The Islamic clergy continued to rely more heavily on the loyal Pasdaran to defend the regime. Moreover, most of the casualties were members of the Pasdaran and Basij volunteers who composed the irregular armed forces. In the late 1980s, in addition to defending the Revolution, Iran continued to follow certain national security policies that had remained constant during the previous four decades.

Historical Background The importance of the armed forces in Iran flows from Iran's long history of successive military empires. For over 2,500 years, starting with the conquests of the Achaemenid rulers of the sixth century B.C., Iran developed a strong military tradition. Drawing on a vast manpower pool in western Asia, the Achaemenid rulers raised an army of 360,000, from which they could send expeditions to Europe and Africa. Iranian early military history boasts the epic performances of such great leaders as Cyrus the Great and Darius I. The last great Iranian military ruler was Nader Shah, whose army defeated the Mughals of India in 1739. Since then, however, nearly all efforts to conquer more territory or check encroaching empires have failed. During much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Iran was divided and occupied by British and Russian military forces. When their interests coincided in 1907, London and St. Petersburg entered into the Anglo-Russian Agreement, which formally divided Iran into two spheres of influence. During World War I, the weak and ineffective Qajar Dynasty, allegedly hindered by the effects of the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1907, could not prevent increasing British and Russian military interventions, despite Iran's declaration of neutrality. In 1918 the Qajar armed forces consisted of four separate foreign-commanded military units. Several provincial and tribal forces could also be called on during an emergency, but their reliability was highly questionable. More often than not, provincial and tribal forces opposed the government's centralization efforts, particularly because Tehran was perceived to be under the dictate of foreign powers. Having foreign officers in commanding positions over Iranian troops added to these tribal and religious concerns. Loyal, disciplined, and well trained, the most effective government unit was the 8,000-man Persian Cossacks Brigade. Created in 1879 and commanded by Russian officers until the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, after which its command passed into Iranian hands, the brigade represented the core of the new Iranian armed forces. Swedish officers commanded the 8,400-man Gendarmerie (later the Imperial Gendarmerie and after 1979 the Islamic Iranian Gendarmerie), organized in 1911 as the first internal security force. The 6,000-man South Persia Rifles unit was financed by Britain and commanded by British officers from its inception in 1916. Its primary task was to combat tribal forces allegedly stirred up by German agents during World War I. The Qajar palace guard, the Nizam,commanded by a Swedish officer, was a force originally consisting of 2,000 men, although it deteriorated rapidly in numbers because of rivalries. Thus, during World War I the 24,400 troops in these four separate military units made up one of the weakest forces in Iranian history. Upon signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany and Turkey on December 15, 1917, Russia put in motion its eventual withdrawal from Iran, preparing the way for an indigenous Iranian military. A hitherto little-known colonel, Reza Khan (later known as Reza Shah Pahlavi, founder of the Pahlavi dynasty), assumed leadership of the Persian Cossacks Brigade in November 1918, after the expulsion of its Russian commanders. In February 1921, Reza Khan and Sayyid Zia ad Din Tabatabai, a powerful civilian conspirator, entered Tehran at the head of 1,500 to 2,500 Persian Cossacks and overthrew the Qajar regime. Within a week, Tabatabai formed a new government and made Reza Khan the army chief. Recognizing the importance of a strong and unified army for the modern state, Reza Khan rapidly dissolved all "independent" military units and prepared to create a single national army for the first time in Iranian history. Riding on a strong nationalist wave, Reza Khan was determined to create an indigenous officer corps for the new army, though an exception was made for a few Swedish officers serving in the Gendarmerie. Within a matter of months, officers drawn from the Persian Cossacks represented the majority. Nevertheless, Reza Khan recognized the need for Western military expertise and sent Iranian officers to European military academies, particularly St. Cyr in France, to acquire modern technical know-how. In doing so, he hoped the Iranian army would increase its professionalism without jeopardizing the country's still fragile social, political, and religious balance. By 1925 the army had grown to a force of 40,000 troops, and Reza Khan, under the provisions of martial law, had gradually assumed control of the central government. His most significant political accomplishment came in 1925 when the parliament, or Majlis, enacted a universal military conscription law. In December 1925, Reza Khan became the commander in chief of the army; with the assistance of the Majlis, he assumed the title of His Imperial Majesty Reza Shah Pahlavi. Reza Khan created the Iranian army, and the army made him shah. Under the shah, the powerful army was used not only against rebellious tribes but also against anti-Pahlavi demonstrations. Ostensibly created to defend the country from foreign aggression, the army became the enforcer of Reza Shah's internal security policies. The need for such a military arm of the central government was quite evident to Reza Shah, who allocated anywhere from 30 to 50 percent of total yearly national expenditures to the army. Not only did he purchase modern weapons in large quantities, but, in 1924 and 1927, respectively, he created an air force and a navy as branches of the army, an arrangement unchanged until 1955. With the introduction of these new services, the army established two military academies to meet the ever-rising demand for officers. The majority of the officers continued to be trained in Europe, however, and upon their return served either in the army or in key government posts in Tehran and the provinces. By 1941 the army had gained a privileged role in society. Loyal officers and troops were well paid and received numerous perquisites, making them Iran's third wealthiest class, after the shah's entourage and the powerful merchant and landowning families. Disloyalty to the shah, evidenced by several coup attempts, was punished harshly. By 1941 the army stood at 125,000 troops -- five times its original size -- and was considered well trained and well equipped. Yet, when the army faced its first challenge, the shah was sorely disappointed; the Iranian army failed to repulse invading British and Soviet forces. London and Moscow had insisted that the shah expel Iran's large German population and allow shipments of war supplies to cross the country en route to the Soviet Union. Both of these conditions proved unacceptable to Reza Shah; he was sympathetic to Germany, and Iran had declared its neutrality in World War II. Iran's location was so strategically important to the Allied war effort, however, that London and Moscow chose to overlook Tehran's claim of neutrality. Against the Allied forces, the Iranian army was decimated in three short days, the fledgling air force and navy were totally destroyed, and conscripts deserted by the thousands. His institutional power base ruined, Reza Shah abdicated in favor of his young son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. In the absence of a broad political power base and with a shattered army, Mohammad Reza Shah faced an almost impossible task of rebuilding. There was no popular sympathy for the army in view of the widespread and largely accurate perception that it was a brutal tool used to uphold a dictatorial regime. The young shah, distancing Tehran from the European military, in 1942 invited the United States to send a military mission to advise in the reorganization effort. With American advice, emphasis was placed on quality rather than quantity; the small but more confident army was capable enough to participate in the 1946 campaign in Azarbaijan to put down a Soviet-inspired separatist rebellion. Unlike its 1925 counterpart, the 1946 Majlis was suspicious of the shah's plans for a strong army. Many members of the parliament feared that the army would once again be used as a source of political power. To curtail the shah's potential domination of the country, they limited his military budgets. Although determined to build an effective military establishment, the shah was forced to accept the ever-rising managerial control of the Majlis. Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, backed by strong Majlis support, demanded and received the portfolio of minister of war in 1952. For the better part of a year, Mossadeq introduced changes in the high command, dismissing officers loyal to the shah and replacing them with pro-Mossadeq nationalists. With the assistance of British and United States intelligence, however, officers dismissed by Mossadeq staged the August 1953 coup d'état, which overthrew the prime minister and returned the shah to power. In a classic housecleaning, several hundred pro-Mossadeq officers were arrested, allegedly for membership in the communist Tudeh Party. Approximately two dozen were executed, largely to set an example and to demonstrate to the public that the shah was firmly in command. Within two years, the shah had consolidated his rule over the armed forces, as well as over the much-weakened Majlis. Separate commands were established for the army, air force, and navy; and all three branches of the military embarked on massive modernization programs, which flourished throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Nonetheless, the shah's military was probably crippled as early as 1955. Mohammad Reza Shah, mistrustful of his subordinates as well as his close advisers, instituted an unparalleled system of control over all his officers. Not only did the monarch make all decisions pertaining to purchasing, promotions, and routine military affairs, but he also permitted little interaction among junior and senior officers. Even less was tolerated among senior officers. No meetings grouping all his top officers in the same room were ever held. Rather, the shah favored individual "audiences" with each service chief; he then delegated assignments and duties according to his overall plans. This approach proved effective for the shah, at least until his downfall in 1979. For the Iranian armed forces, it proved devastating. As internal security agencies assumed the critical role of maintaining public order, the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces (IIAF) were charged with defending the country against foreign aggression. First among threats was the Soviet Union, which shares a 2,000-kilometer border with Iran. The shah feared that Moscow would try to again access to warm-water port facilities, a Russian goal since Peter the Great, and seek to destabilize what the Soviets surely perceived to be a pro-Western, if not pro-American, regime. The majority of Iranian troops, therefore, were stationed in the north for the better part of the early 1960s. The resulting high level of tension between two mismatched neighboring forces was not a satisfactory arrangement for the politically and militarily astute monarch. Taking a pragmatic approach, the shah pursued economic cooperation to improve relations with the Soviet Union and thereby reduced military tensions along the border. Having softened Iran's Cold War rhetoric in relation to Moscow, the shah focused his attention on the Persian Gulf. When in 1971 Britain terminated its treaties of protection with the several small Arab shaykhdoms or amirates of the Arabian Peninsula, the shah's primary security concerns shifted to the border with Iraq. When petroleum exports from the Gulf expanded rapidly in the 1970s and British withdrawal from the conservative shaykhdoms created a security vacuum, the Iranian military expanded its plans to include the defense of sea-lanes, especially the Strait of Hormuz, although navigation through the strait generally takes place entirely in Oman's territorial waters. Iran has always considered the forty-one-kilometer-wide strait vital to its oil exports and, since 1968, has made every effort to exert as much influence as possible there. The shah referred to the strait as Iran's "jugular vein," and the revolutionary regime has been similarly concerned with its security. In March 1975, Iran reached a geographic-political agreement with Iraq. This pact, called the Algiers Agreement, accomplished two important military objectives. First, because the existence of the agreement allowed Iran to terminate aid to the Kurdish rebels in Iraq, Iran could deploy more of its forces in areas other than the Iraqi border. Second, Baghdad's acceptance of Iran's boundary claim to a thalweg (the middle of the main navigable channel) in the Shatt al Arab settled a security issue, freeing the Iranian navy to shift its major facilities from Khorramshahr on the Iraqi border to Bandar Abbas near the strait and to upgrade its naval forces in the southern part of the Gulf. Despite frequent public expressions of reserve, the weaker conservative

Arab monarchies of the Persian Gulf supported the shah's military mission

of guaranteeing

freedom of navigation in and through the Gulf. They strongly objected,

however, to Iran's military occupation in November 1971 of the islands

of Abu Musa,

belonging to Sharjah, and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs, belonging to

Ras al Khaymah. These two members of the United Arab Emirates could offer

no resistance

to Tehran's swift military action, however. The Iranian navy used its

Hovercraft to transport occupying troops, and it eventually installed military

facilities on two of

the islands. Despite its earlier agreement to respect Sharjah's claim

to Abu Musa, Tehran justified the occupation of Abu Musa and the Tunbs

on strategic grounds.

This action was only the precursor of other regional operations by which a strong Iranian military would deter foreign, especially Soviet or Soviet-inspired, incursions into the Gulf. Twice, during the 1970s, the shah provided military assistance -- to Oman and Pakistan -- to overcome internal rebellions. By doing so, he established Iran as the dominant regional military power. The most significant combat operation involving Iranian (along with British and Jordanian) troops took place in Oman's Dhofar Province. Iran aided Sultan Qabus in fighting the Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman, which was supported by the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) and the Soviet Union. Starting with an initial force of 300 in late 1972, the Iranian contingent grew in strength to 3,000 before its withdrawal in January 1977. The shah was proud that his forces had participated in the defeat of the guerrilla rebellion, even though the performance of Iranian troops in Oman was mixed. The air force received the most favorable reports from the battle zone. Reconnaissance flights provided valuable information, and helicopters proved effective in the rugged Dhofar region. Ground forces fared less well, suffering significant casualties, with 210 Iranian soldiers killed in 1976 alone. The high casualty rate was attributed to the overall lack of combat experience. Nearly 15,000 Iranian soldiers were rotated through Oman during the five-year period. In 1976 Iranian counterinsurgency forces, relying on helicopter support, were deployed in Pakistan's Baluchistan Province to combat another separatist rebellion. This operation, albeit small and limited, was of considerable concern to Iran, which had a large Baluch population of its own. The shah sought to buy insurance against a possible insurrection in Iran by helping Pakistan crush a Baluch uprising. The shah continued to assist his allies in Oman and Pakistan after 1977. More important, Iran had served notice that it would engage its military to preserve the status quo in the Persian Gulf region, a status quo that was heavily tilted to its advantage. On more than one occasion, the shah stated that he would not refrain from maintaining the security of the Gulf, whether or not his troops were invited to intervene. Iran had also come of age in the larger context of the Middle East. Between 1958 and 1978 Iran participated in war games conducted under the auspices of the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), which grouped Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and Britain (with the United States participating as an observer). Although CENTO declined in significance over the years, its military exercises, especially the yearly Midlink maritime maneuvers, provided useful training for the Iranian armed forces. The shah also participated in United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions, sending a battalion to the UN buffer zone in the Golan Heights as part of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force in 1977. The bulk of this force also served in southern Lebanon following the Israeli invasion of 1978. The Iranian contingent in the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon was withdrawn in late 1978, however, following several desertions by Shia Muslim soldiers sympathetic to the local population. On January 16, 1979, as the shah was preparing to leave Iran for the

last time, he was still confident that his army could and would handle

any internal disturbances.

Still under the impression that the Soviet Union and Iraq were the

greatest threats to his country, he left behind a United States-designed

army prepared for external

rather than domestic requirements.

The Revolutionary Period Lack of leadership at the general staff level and below in the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces (IIAF) had literally frozen the military between December 1978 and February 1979. In the melee of the Revolution, mob scenes were frequent; on several occasions the army fired on demonstrators, killing and injuring many civilians, the most famous such encounter occurring at Jaleh Square in Tehran. In response to these incidents, army units of the IIAF, responsible for law and order in Tehran and other large cities, were attacked by mobs. Within days after the Revolution's success, several religious leaders, however, claimed that the armed forces had "joined the nation" or "returned to the nation" and cautioned against indiscriminate vengeance against the military.

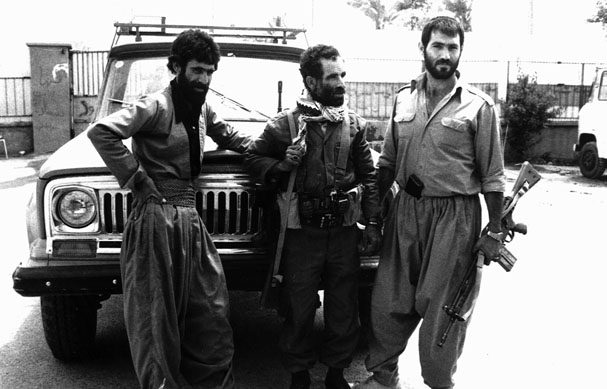

Members of the shah's Imperial Iranian Armed Forces The government took prompt steps to reconstitute the armed forces, weakened in both numbers and morale. Contrary to the general perception in 1979 and 1980, Khomeini did not seek the disintegration of the armed forces but rather wished to remold the shah's army into a loyal national Islamic force. Troops that had heeded Khomeini's appeal to disband were called back in March 1979. A new command group established in February 1979 was composed of nine officers with impeccable revolutionary credentials: they had all been imprisoned under the shah for different reasons. Khomeini relied on the advice of Colonel Nasrollah Tavakkoli, a retired Special Forces officer, to recruit ideologically compatible officers for the armed forces. General staff personnel were all called back to coordinate the nascent reorganization; division and brigade command positions were promptly filled by loyal and reliable officers. The Imperial Guard, the Javidan Guard, and the Military Household of the shah were the only organizations that were permanently disbanded. The revolutionary government decided to formulate as clearly as possible the functions and roles of the armed forces, particularly in relation to internal security. In contrast to the shah's regime, it entrusted internal security functions to the newly established Pasdaran. Pasdaran clergy were also engaged to disseminate Islamic justice and were assigned to units of the armed forces to help communicate Khomeini's instructions and to provide religio-political indoctrination. Much of this early cooperation was an extension of the military's existing support for the Revolution. For example, even though the head of the air force, General Amir Hosain Rabii, opposed the Revolution, many air force cadets and young homafars (skilled military technical personnel) supported it. Revolutionary groups that had played prominent roles in the seizure of power, however, were hostile to the military. These included the Mojahedin (Mojahedin-e Khalq, or People's Struggle), the Fadayan (Cherikha-ye Fadayan-e Khalq, or People's Guerrillas), and even the Tudeh, which called for a drastic purge of the military. The Mojahedin, especially, threatened the military's position because it had captured the Tehran arms factory and government arsenal depots and was thus armed. Moreover, the Mojahedin quickly organized into "councils" and recruited personnel in military posts throughout the country, seeing themselves as the military core of the new order. These councils were then turned into debating forums where conscripts could air past grievances against officers. The Tudeh, for its part, called on the government to return to active duty several hundred officers dismissed or imprisoned under the shah for their membership in the Tudeh. The provisional government recognized the threat implicit in these demands. In the absence of a centralized command system, the military balance of power would eventually tilt toward the heavily armed guerrilla groups of the left. Hojjatoleslam Ali Khamenehi (who became president of Iran in 1982) and many of the leading ayatollahs were very suspicious of the leftist guerrillas. The members of the Revolutionary Council (a body formed by Khomeini in January 1979 to supervise the transition from monarchy to republic) would have preferred to balance the power of the leftist guerrillas with that of the Pasdaran, but the Pasdaran was in its formative stage and had neither the necessary strength nor the training. The ultimate elimination of the Mojahedin, Fadayan, and Tudeh was a foregone conclusion in the ideological framework of an Islamic Iran. To this end, revolutionary leaders both defended and courted the military, hoping to maintain it as a countervailing force, loyal to themselves. In one of his frequent public pronouncements, Khomeini praised military service as "a sacred duty and worthy of great rewards before the Almighty" and solicited military support for his regime, declaring that "the great Iranian Revolution is more in need of defense and protection than at any other time." Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan denounced guerrilla demands for a full-scale purge of the military. In the end, the leadership decided in February 1979 that a purge of the armed forces would be undertaken, but on a limited scale, concentrating on "corrupt elements." The purge of the military started on February 15, 1979, when four general officers were executed. Two groups were purged, one consisting of those elements of the armed forces that had been closely identified with the shah and his repression of the revolutionary movement and the other including those that had committed actual crimes of violence, particularly murder and torture, against supporters of the Revolution. A total of 249 members of the armed forces, of whom 61 were SAVAK (Sazman-e Ettelaat va Amniyat-e Keshvar, the shah's internal security organization) agents, were tried, found guilty, and executed between February 19 and September 30, 1979. Significant as this figure is, it represented only a small percentage of military personnel. Apart from the replacement of senior officers, various structural changes were introduced in the aftermath of the Revolution. But because of the lack of leadership at headquarters, command and control were at best tenuous. Local commanders exercised unprecedented autonomy, and integration of the regular armed forces with the Pasdaran was not even considered. Lack of coordination within the Pasdaran and between it and regular army personnel resulted in shortages for the Pasdaran of desperately needed supplies, ranging from daily rations to ammunition; such supplies usually found their way only to army depots. In isolated areas, cooperation between the Pasdaran and the regular military eventually emerged. For example, in West Azarbaijan, prorevolutionary officers in the 64th Infantry Division in Urumiyeh (also cited as Urmia to which it has reverted after being known as Rezaiyeh under the Pahlavis) extended a helping hand to the Pasdaran in the latter's efforts to crush an uprising. The 64th Infantry Division's leading officers, including Colonel Qasem Ali Zahirnezhad and Colonel Ali Seyyed-Shirazi, were strong advocates of cooperation. They made proposals in which they argued that the Pasdaran and the regular military should be completely integrated at the operational level while maintaining separate administrations. They envisaged joint staffs at divisional and higher echelons, joint logistical systems, and joint procurement of equipment. By accepting logistical assistance from the military, the Pasdaran could become combat ready. From the regular armed forces' perspective, cooperation would turn members of the Pasdaran into professional soldiers. The process would also create a level of mutual dependence, thereby preventing antimilitary measures. Airings of proposals for similar cooperative measures received sympathy from some officers at the National Military Academy, where Commandant Colonel Musa Namju, expanding on Colonel Zahirnezhad's and Colonel Seyyed-Shirazi's earlier proposals, wrote several widely read documents. Little or no support came from Minister of Defense Mostofa Ali Chamran, who was more concerned with the impact that a full and rapid reorganization of the military might have on the Revolution. Neglected for over a year, Iran's ground forces fared poorly during the first stages of the Iran-Iraq War. Ironically, logistical shortcomings rather than desertions or combat defects were the problem. By the end of 1980, Iranian leaders finally recognized supply deficiencies and the more important command-and-control problems that were crippling the military. Colonel Namju resurrected the group proposals, and Chamran appointed Colonel Zahirnezhad and Colonel Seyyed-Shirazi to senior command and staff positions at the front. In Tehran, President Abolhasan Bani Sadr attempted to gain control of the armed forces but failed for several reasons. Above all, Khomeini would not permit the Supreme Defense Council (SDC) to be dominated by any faction, and he was not prepared to make an exception for Bani Sadr. Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Rajai, Bazargan's successor, and his Islamic Republican Party (IRP) allies, concerned with the Revolution as much as the war, were adamant in their opposition to Bani Sadr's unilateral decisions. Bani Sadr was also weakened by his frequent interference in purely military affairs (in which his poor judgment in military matters became evident) as well as by competition with clergy members. Despite the rift between Bani Sadr and the IRP, the SDC appointed him supreme commander over all regular and paramilitary units. His control of the military was tenuous, however, because by early 1981 IRP members were demanding representation at the senior levels of command. In addition, the front as an operational area was organized into subordinate field sectors and operational sectors, with little official liaison among the different service staffs. Moreover, the war effort was going poorly. Bani Sadr's ouster from the presidency and Chamran's death at the front galvanized the Urumiyeh group to push for implementation of the reorganization proposals. Colonel Namju was the new defense minister, and reorganization of the command system received his full support. By September 1981, SDC approval was ensured and coordination with the Pasdaran initiated. Deputy Commander in Chief of the Pasdaran Kolahduz supervised the first operational integration of the regular military with the Pasdaran. Even the air force relented, and Brigadier General Javad Fakuri authorized additional close air support for ground forces. On September 24, 1981, a new command and control system was finalized at a Tehran meeting hosted by Pasdaran commander in chief Mohsen Rezai, who agreed to test the new proposals. An operation was launched to liberate Abadan and force the Iraqis to the west bank of the Karun River. Within four days, Iran's coordinated attack was successful, and the Iraqis retreated. For the first time since the outbreak of hostilities, a full-scale integration at the staff level produced positive results. On September 29, 1981, several high-ranking military leaders, including

Colonel Namju and Kolahduz, were killed in an airplane crash. Colonel Zahirnezhad,

promoted to brigadier general, took over as chief of the Joint Staff

of the armed forces, and Colonel Seyyed-Shirazi took Zahirnezhad's post

as commander of

armed forces. These appointments ensured the full implementation of

the new command system.

Command and Control According to Article 110 of the 1979 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the faqih is empowered to appoint and dismiss the chief of the Joint Staff, the commander in chief of the Pasdaran, two advisers to the SDC, and the commanders in chief of ground, naval, and air forces on the recommendation of the SDC. He is also authorized to supervise the activities of the SDC and to declare war and mobilize the armed forces on the recommendation of the SDC. As faqih, Khomeini, although maintaining the role of final arbiter, has delegated the post of commander in chief to the president of the Republic. In addition to specifying the duties of the commander in chief, Article 110 establishes the composition of the SDC as follows: president of the country, prime minister, minister of defense, chief of the Joint Staff of the armed forces, commander in chief of the Pasdaran, and two advisers appointed by the faqih. Other senior officials may attend SDC meetings to deliberate national defense issues. In the past, the minister of foreign affairs, minister of interior, minister of the Pasdaran and his deputy, air force and navy commanders in chief, War Information Office director, and others have attended SDC meetings. The ground forces commander in chief, Colonel Seyyed-Shirazi, is a member of the SDC as a representative of the military arm for the faqih, whereas Majlis speaker Hojjatoleslam Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani is representative of the political arm for the faqih. Iran's strategic planning and the establishment of its military and defense policies are the responsibilities of the SDC, which has representatives at operational area and field headquarters to provide political and strategic guidance to field commanders. SDC representatives may also veto military decisions. But reports in 1987 indicated that SDC orders to regional representatives have been modified to limit the heavy casualty rates caused by their inappropriate advice. Inexperienced nonmilitary religious advisers have seen their interference in purely technical matters dramatically curtailed. The Urumiyeh reorganization proposals recognized the administrative separation of the services as part of Iran's political reality. Consequently, as of 1987 there were two chains of command below the SDC, one administrative and the other operational. To some extent this dual chain of command existed because the revolutionary government had retained a modified version of the organizational structure of the IIAF, which was modeled on the United States division of powers between the administrative functions of the service secretaries and the operational functions of the secretary of defense and chiefs of staff. In addition, the IRP leaders wanted to limit friction between the regular military and the Pasdaran. According to Speaker Hashemi-Rafsanjani, the service commanders in chief, the minister of defense, and the minister of the Pasdaran were removed from the operational chain to avoid further friction between the two groups. In 1987 the Ministry of Defense continued to handle administrative matters for the regular armed forces. The chain of command flowed from senior unit commanders (division, wing, and fleet) to intermediate-echelon service commanders and to service commanders in chief and their staffs. Similarly, the Ministry of the Pasdaran handled the administrative affairs of the Pasdaran. The chain of command flowed from senior unit commanders (operational brigades in the case of combat units) to the ministry staff officers. In the case of internal security units, the chain of command went from local commanders to provincial commanders (who were colonels) and then to provincial general commanders (who were generals). The Joint Staff of the armed forces, composed of officers assigned from

the various services, the Pasdaran, the National Police, and the Gendarmerie,

was

responsible for all operational matters. Its primary tasks included

military planning and coordination and operational control over the regular

services, combat units of

Staff members of J1 -- Personnel and Administration -- conducted planning and liaison duties with their counterparts at the ministries of defense, interior, and the Pasdaran. They also supervised budgeting and financial accountability and the preparation of operational budgets for Majlis approval for all the armed services. Personnel of J2 -- Intelligence and Security -- carried out operational control for intelligence planning, intelligence operations, intelligence training, counterintelligence, and security for all elements of the armed forces. They also handled liaison with the komitehs (revolutionary committees) for internal security matters and with SAVAMA for foreign intelligence. Staff members of J3 -- Operations and Training -- conducted training, operational planning, operations, and communications. The operational planning and operations sections were further divided into eleven subsections for planning and coordination of the services, including: the Iranian Islamic Ground Forces (IIGF), IIGF Aviation, IIGF Chemical Troops, IIGF Artillery Troops, IIGF Engineer Troops, Iranian Islamic Air Force (IIArF), Iranian Islamic Navy (IIN), IIN Aviation, the Pasdaran, the Gendarmerie, and the National Police. Personnel of J4 -- Logistics and Support -- coordinated and provided liaison for the services. Primary responsibility for logistics and supply rested with the services through the ministries of defense, interior, and the Pasdaran; collection and coordination of supplies and coordination of transportation to the war front, however, remained under the control of J4. Staff members of J5 -- Liaison -- handled liaison and coordination with nonmilitary organizations and with those military organizations not covered by Joint Staff-level arrangements. Organizations covered by J5 included the Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of the Pasdaran, Office of the Prime Minister, Council of Ministers' Secretariat, SDC, Majlis (particularly the Defense and Foreign Affairs Committee), the Foundation for Popular Mobilization, the Foundation for the Disinherited, the Foundation for Martyrs (Bonyad-e Shahid), the Foundation for War Victims, and the Crusade for Reconstruction (Jihad- e Sazandegi or Jihad). The office of the staff judge advocate provided legal counsel to the Joint Staff and facilitated liaison with the revolutionary prosecutor general and the military tribunal system of the armed forces. The Political-Ideological Directorate (P-ID) staff members operated the political-ideological bureaus of the Joint Staff components and the political-ideological directorates and bureaus of the operational commands. This office also developed and disseminated political-ideological training materials, in close cooperation with the Foundation for the Propagation of Islam and the Islamic associations of the services. Finally, P-ID members conducted liaison duties between the Joint Staff and the Islamic Revolutionary Court of the Armed Forces. Members of the Inspectorate General handled oversight functions over the staff components and liaison with the inspectors general of the operational commands. Special Office for Procurements staff members controlled and coordinated procurement of military equipment and supplies from foreign sources through the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of the Pasdaran, the Ministry of Commerce and Foreign Trade, and the Central Bank of Iran. In general, operational area commands were subordinate to the Joint

Staff, and each armed force component was subordinate to the operational

area command in

The Western Operational Area Command was similar in structure to the armed forces Joint Staff except that it was also the lowest operational echelon at which naval forces were integrated into combined-services operations and planning. Although operational area command Joint Staff members exercised operational control over all troops within their area, they were subject to several constraints. Generally speaking, Pasdaran, Gendarmerie, and National Police units operating in an internal security mission, particularly against insurgents, were detached from the operational area command and subordinated to the senior Pasdaran commander in the province in which they were engaged. Air and naval units continued to be partially controlled by their service commanders and responded to the Western Operational Area Command Joint Staff through specialized liaison staffs. The commander of the operational area was further burdened by the presence at his headquarters of an SDC representative and a personal representative of Khomeini. Both of these influential individuals could effectively take any matter over the commander's head to higher authority. In 1987 the SDC representative in the Western Operational Area Command was also the Pasdaran commander for the operational area command, a situation that further complicated the command and control system. Below the Operational Area Command were four field headquarters (FHQ), code-named FHQ Karbala, FHQ Hamzeh Seyyed ash Shohada, FHQ Ramadah, and FHQ An Najaf. The FHQs were organized on the model of the Western Operational Area Command except that they did not have naval integration. Subordinate to each FHQ were from three to eight operational sectors. Each operational sector did not necessarily have its own air support unit. Additional echelons consisting of a commander and staff drawn from the Joint Staff of the participating FHQs could be created during major offensives. The purpose of these echelons was to overcome logistical shortcomings, concentrate and deploy forces as needed, and combine the services, particularly the naval forces, in offensive operations. The reorganization of the command-and-control system could largely be

attributed to the Urumiyeh proposals. The war with Iraq naturally increased

the level of

integration, particularly between regular military officers commanding

Pasdaran units and Pasdaran officers commanding regular military units.

Logistical problems

also came under increasing scrutiny because of the war. The military's

weak infrastructure required the centralization of logistics and supply.

The sophisticated

computer inventory and accounting systems of the ground, air, and naval

logistical commands had been sabotaged during the Revolution, and the country

lost

valuable time while bringing these systems back into service. Improvements

in logistical support proved quite rewarding, revealing, for example, that

Iran possessed

twice as many critical spare parts for its aircraft as were previously

believed to exist. Nevertheless, the Iranian armed forces faced a logistical

dilemma in deploying

supplies to troops at the front; lack of maintenance skills translated

into a decreased repair and salvage capacity, creating serious bottlenecks.

Vehicles in need of

repair had to be transported to repair centers hundreds of kilometers

from the front, along stretches of poorly maintained roads and railroads.

Under such

circumstances cannibalization of damaged equipment for spare parts,

particularly for sophisticated equipment, became the norm. Without a solution

in sight, Iranian

authorities relied on the "down time" between major offensives to resupply

units before resuming offensive operations. This practice further prolonged

the war,

because multiphased operations could not be launched and sustained.

Organization, Size, and Equipment As faqih, Khomeini is constitutionally designated supreme commander

of the armed forces. He has delegated his powers to the president, who

may in turn delegate

authority as required. Important decisions regarding defense policies

are made by the SDC, which combines senior members of the armed services

with senior

members of the government.

Army In 1979, the year of the shah's departure, the army experienced a 60-percent desertion from its ranks. By 1986 the regular army was estimated to have a strength of 305,000 troops. In the fervor of the Revolution and in the light of numerous changes affecting conscripts and reservists, the army underwent a structural reorganization. Under the shah, the army had been deployed in 6 divisions and 4 specialized combat regiments supported by more than 500 helicopters and 14 Hovercraft. An 85-percent readiness rate was usually credited to the force, although some outside observers doubted this claim. Following the Revolution the army was renamed the Islamic Iranian Ground Forces (IIGF) and in 1987 was organized as follows: three mechanized divisions, each with three brigades, each of which in turn was composed of three armored and six mechanized battalions; seven infantry divisions; one airborne brigade; one Special Forces division composed of four brigades; one Air Support Command; and some independent armored brigades including infantry and a "coastal force." There was also in reserve the Qods battalion, composed of ex-servicemen. After the mid-1970s, military manpower was unevenly deployed. Nearly 80 percent of Iran's ground forces were deployed along the Iraqi border, although official sources maintained that the military was capable of rapid redeployment. Although air force transports were used extensively, redeployment was slow after the start of the war. The Mashhad division headquarters, in the eastern part of the country, has remained important because of Soviet military operations in Afghanistan and resulting Afghan migration into Iran. In the past, Iran purchased army equipment from many countries, including the United States, Britain, France, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), Italy, and the Soviet Union. By late 1987, Iran had diversified its acquisitions, obtaining arms from a number of suppliers. Among them were the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), China, Brazil, and Israel. The diversity of the weapons purchased from these countries greatly complicated training and supply procedures, but, faced with a war of attrition and a continuous shortage of armaments, Iran was willing to purchase from all available sources. The IIGF operated almost 1,000 medium tanks in 1986. Although a large number were British-made Chieftains and American-made M-60s, an undetermined number of Soviet-made T-54 and T-55s, T-59s, T-62s, and T-72s were also part of the inventory, all captured from the Iraqis or acquired from North Korea and China. There was also a complement of fifty British-made Scorpion light tanks. Several hundred Urutu and Cascavel armored fighting vehicles from Brazil joined American-made M-113s and Soviet-made BTR-50-60s. An undetermined number of Soviet-made Scud surface-to-surface missiles were acquired from a third country, believed to be Libya. And in November 1986, the United States revealed that it had supplied the Iranian military with Hawk surface-to-air missiles and TOW antitank missiles via Israel. The army's aviation unit, whose main operational facilities were located

at Esfahan, was largely equipped with United States aircraft, although

some helicopters were

of Italian manufacture. In 1986 army aviation operated some 65 light

fixed-wing aircraft, but its strength lay in its estimated 320 combat helicopters,

down from 720

in 1980.

Navy The Iranian navy has always been the smallest of the three services, having about 14,500 personnel in 1986, down from 30,000 in 1979. Throughout the 1970s, the role of the navy had expanded as Iran recognized the need to defend the region's vital sea-lanes. In 1977 the bulk of the fleet was shifted from Khorramshahr to the newly completed base at Bandar-e Abbas, the new naval headquarters. Bushehr was the other main base; smaller facilities were located at Khorramshahr, Khark Island, and Bandar-e Khomeini (formerly known as Bandar-e Shahpur). Bandar-e Anzelli (formerly known as Bandar-e Pahlavi) was the major training base and home of the small Caspian fleet, which consisted of a few patrol boats and a minesweeper. The naval base at Bandar Beheshti (formerly known as Chah Bahar) on the Gulf of Oman had been under construction since the late 1970s and in late 1987 still was not completed. Smaller facilities were located near the Strait of Hormuz. The Navy's airborne component, including an antisubmarine warfare (ASW) and minesweeping helicopter squadron and a transport battalion, continued to operate in 1986 despite wartime losses. Of six P-3F Orion antisubmarine aircraft, perhaps two remained operational, and of twenty SH-3D ASW helicopters, possibly only ten were airworthy. Despite overall losses, the navy increased the number of its marine battalions from two to three between 1979 and 1986. Entirely of foreign origin, Iran's naval fleet has suffered major losses since the beginning of the war, when it was made up of American- and British-made destroyers and frigates, and some sixty smaller vessels and one of the largest Hovercraft fleets in the world. The Hovercraft had been expressly chosen to operate in the shallow waters of the Persian Gulf and proved useful in the 1971 occupation of Abu Musa and the Tunbs. After the cancellation of foreign orders in 1979, the rapid matériel advance of the navy was halted. For example, the shah's government had ordered six Spruance-class destroyers equipped for antiaircraft operations and three diesel-powered Tang-class submarines from the United States. Washington canceled the sale of these vessels, selling the submarines to Turkey and absorbing the destroyers into the United States Navy. In 1979 Khomeini also canceled an order for six type-209 submarines from West Germany. What naval vessels remained in 1987 suffered from two major problems -- lack of maintenance and lack of spare parts. After the departure of British-United States maintenance teams, the Iranian navy conducted only limited repairs, despite the availability of a completed Fleet Maintenance Unit at Bandar-e Abbas; consequently, several ships were laid up. Lack of spare parts also plagued the navy more than other services, because Western naval equipment was less widely available on world arms markets than other equipment. Iran's ambitious plans for escort and patrol capabilities in the Persian

Gulf and the Indian Ocean may not be realized until the Bandar Beheshti

naval facility is

completed. The country's interest in navigation through the Strait

of Hormuz has not diminished, as the contemplated deployment of Chinese-made

Silkworm HY-2

surface-to-surface missiles on Larak Island in 1987 clearly indicated.

This development underscored Iran's interest in Gulf waters and the navy's

role, along with that

of Pasdaran units, in protecting them or in denying them to others.

Air Force The shah's air force had more than 450 modern combat aircraft, including top-of-the-line F-14 Tomcat fighters and about 5,000 well-trained pilots. By 1979 the air force, numbering close to 100,000 personnel, was by far the most advanced of the three services and among the most impressive air forces in the developing world. Reliable information on the air force after the Revolution was difficult to obtain, but it seems that by 1987 a fairly large number of aircraft had been cannibalized for spare parts. Before the Revolution, the air force was organized into fifteen squadrons with fighter and fighter-bomber capabilities and one reconnaissance squadron. In addition, one tanker squadron, and four medium and one light transport squadron provided impressive logistical backup. By 1986 desertions and depletions led to a reorganization of the air force into eight squadrons with fighter and fighter-bomber capabilities and one reconnaissance squadron. This reduced force was supported by two joint tanker-transport squadrons and five light transport squadrons. Some seventy-six helicopters and five surface-to-air missile (SAM) squadrons supplemented this capability. Air force headquarters was located at Doshan Tapeh Air Base, near Tehran. Iran's largest air base, Mehrabad, outside Tehran, was also the country's major civil airport. Other major operational air bases were at Tabriz, Bandar-e Abbas, Hamadan (Shahroki Air Base), Dezful (Vahdati Air Base), Shiraz, and Bushehr. Since 1980 air bases at Ahvaz, Esfahan (Khatami Air Base), and Bandar Beheshti have also become operational. Throughout the 1970s, Iran purchased sophisticated aircraft for the air force. The acquisition of 77 F-14A Tomcat fighters added to 166 F-5 fighters and 190 F-4 Phantom fighter-bombers, gave Iran a strong defensive and a potential offensive capability. Before the end of his reign, the shah placed orders for F-16 fighters and even contemplated the sharing of development costs for the United States Navy's new F-18 fighter. Both of these combat aircraft have been dropped from the revolutionary regime's military acquisitions list, however. When the Iran-Iraq War started in 1980, Iran's F-14s, equipped with Phoenix missiles, capable of identifying and destroying six targets simultaneously from a range of eighty kilometers or more, inflicted heavy casualties on the Iraqi air force, which was forced to disperse its aircraft to Jordan and Oman. The capability of the F-14s and F-4s was enhanced by the earlier acquisition of a squadron of Boeing 707 tankers, thereby extending their combat radius to 2,500 kilometers with in-flight refueling. By 1987, however, the air force faced an acute shortage of spare parts and replacement equipment. Perhaps 35 of the 190 Phantoms were serviceable in 1986. One F-4 had been shot down by Saudi F-15s, and two pilots had defected to Iraq with their F-4s in 1984. The number of F-5s dwindled from 166 to perhaps 45, and the F-14 Tomcats from 77 to perhaps 10. The latter were hardest hit because maintenance posed special difficulties after the United States embargo on military sales. China and North Korea with their "independent" policies on arms sales, were the only countries willing to sell Iran combat airplanes. Iran had acquired two Chinese-made Shenyang J-6 trainers in 1986. Unconfirmed reports in 1987 indicated that Iran was receiving Shenyang F-6s (Chinese-built MiG-19SFs), and that Iranian pilots were receiving training in North Korea. The reconnaissance squadron has also struggled to perform its duties with limited equipment. Once flying close to thirty-four aircraft, by late 1987 it may have been reduced to eight, having converted five Tomcats to serve in a noncombat role. It was not clear whether these five airplanes were in addition to the ten in the interceptor squadrons. Given the technical sophistication of reconnaissance aircraft, it was almost impossible to acquire from non-Western sources new ones capable of performing to Iranian standards. The only substantial acquisition was the purchase of forty-six Pilatus PC-7s from Switzerland. Iran requested three Kawasaki C-1 transports and a 3D air defense radar system from Japan, but this transaction did not appear to have materialized by 1987. Reports also indicated that Iran had placed with Argentina an order for thirty Hughes 500D helicopters. From its inception, the air force also assumed responsibility for air defense. The existing early warning systems, built in the 1950s under the auspices of CENTO, were upgraded in the 1970s with a modern air defense radar network. To complement the ground radar component and provide a blanket coverage of the Gulf region, the United States agreed to sell Iran seven Boeing 707 airborne warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft in late 1977. Because of the Revolution, Washington canceled the AWACS sale, claiming that this sensitive equipment might be compromised. Finally, the air force's three SAM battalions and eight improved Hawk battalions were reorganized in the mid-1980s (in a project involving more than 1,800 missiles) into five squadrons that also contained Rapiers and Tigercats. Washington's sale of Hawk spare parts and missiles in 1985 and 1986 may have enhanced this capability. The air force's primary maintenance facility was located at Mehrabad

Air Base. The nearby Iran Aircraft Industries, in addition to providing

main overhaul backup

for the maintenance unit, has been active in manufacturing spare parts.

Source and Quality of Manpower Armed forces manpower increased substantially throughout the 1970s as the shah implemented Iran's "guardian" role in the Gulf. Following the outbreak of the Revolution, there was a sharp drop in the number of military personnel, which in 1982 stood at 235,000, including the Pasdaran but excluding reserves. In contrast, total military personnel, including the Pasdaran but excluding reserves, stood at 704,500 in 1986. In addition to active-duty personnel, some 400,000 veterans, organized in reserve units after the outbreak of the war, were subject to recall to duty. Two-thirds of army personnel were conscripts; in the air force and navy, the majority were volunteers. The National Military Academy was the largest single source of commissioned officers in the 1970s, but since 1980 a significant number of commissions have been awarded for wartime heroism and leadership at the front. Although air force and navy officers had attended military academies or participated in cadet programs in the United States, Britain, or Italy before 1979, few foreign contacts have been recorded since the Revolution. In the few instances in which contact was established, it was with Asian states, namely China and North Korea. Unlike the army, the air force and navy have experienced high attrition, and it must be assumed that operations have been streamlined to be effective with fewer personnel. Class differences in the armed forces remained virtually undisturbed by the Revolution. Commissioned officers came from upper class families, career noncommissioned and warrant officers from the urban middle class, and conscripts from lower class backgrounds. By 1986, an increasing segment of the officer corps came from the educated middle class, and a significant number of lower middle-class personnel were commissioned by Khomeini for leadership on the battlefield. Iran's 1986 population of approximately 48.2 million (including approximately 2.6 million refugees) gave the armed forces a large pool from which to fill its manpower needs, despite the existence of rival irregular forces. Of about 8 million males between the ages of eighteen and fourty-five, nearly 6 million were considered physically and mentally fit for military service. Revolutionary leaders have repeatedly declared that Iran could establish an army of 20 million to defend the country against foreign aggression. Since the beginning of 1986, women have also been encouraged to receive military training, although no women were actually serving in the regular armed forces as of late 1987. The decision to encourage women to join in the military effort may indicate an increasing demand for personnel or an effort to gain increased popular support for the Revolution. It could also mean that conscription was not replacing war losses or retirements. Compulsory conscription has been in effect since 1926, when Reza Shah's Military Service Act was passed by the Majlis. All males must register at age nineteen and begin their military service at age twenty-one; the law, however, is of limited significance in view of government pressures for volunteer enlistments in military units at an earlier age. According to the act, the total period of service is twenty-five years, divided as follows: two years of active military service, six years in standby military service for draftees, then eight years in first-stage reserve and nine years in second-stage reserve. In 1984 the Majlis passed the new Military Act. It amended conscription laws to reduce the high number of draft dodgers. Newspapers have carried reports of people caught trying to buy their way out of military service, at an unofficial figure of about US$8,000 for forged exemption documents. Under the prerevolutionary law, temporary or permanent exemptions were provided for the physically disabled, hardship cases, convicted felons, students, and certain professions. Draft evaders were subject to arrest, trial before a military court, and imprisonment for a maximum of two years after serving the required two years of active duty. Few draft dodgers, if any, were sent to jail; the normal procedure was to fine them the equivalent of US$75 (1986 exchange rate). Under the 1984 law, draft evaders were subject to restrictions for a period of up to ten years. They could be prevented from holding a driver's license, running for elective office, registering property ownership, being put on the government payroll, or receiving a passport, in addition to being forced to pay fines and/or receive jail sentences. Exemptions were given only to solve family problems. Moreover, all exemptions, except for physical disabilities, were only for five years. Those seeking relief for medical reasons had to serve but were not sent on combat duty. Under the amended law, men of draft age were subject to conscription, whether in war or peace, for a minimum period of two years and could be recalled as needed. In the past, a consistent weakness of the armed forces had been the high illiteracy rate among conscripts and volunteers. This reflected the country wide illiteracy rate, which stood at 60 percent in 1979. Compounding this dilemma, many conscripts came from tribal areas where Persian was not spoken. Thus, the military first had to teach the conscripts Persian by instituting extensive literacy training programs. By 1986 the country's overall literacy rate was estimated at 50 percent, a dramatic improvement. This gain was also reflected in the regular armed forces. Of the three services, the air force fared best in this respect, as it had always done. Yet even the air force, which had developed training facilities for support personnel and homafars, was short of its real requirements. With the 1979 withdrawal of foreign military and civilian advisers, particularly from the United States and Pakistan, the operation, maintenance, and logistical functioning of armed forces' equipment was hampered by a critical shortage of skilled manpower. As purchases from non-Western countries increased, Iran came to rely on Chinese, Syrian, Bulgarian (unconfirmed), and North Korean instructors and those from the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), among others. In 1987 the impressive progress of the regular armed forces was counterbalanced

by manpower shortages. Without the support of large numbers of irregular

forces

and volunteers, it was difficult to foresee how this shortage might

be overcome.

Foreign Influences in Weapons, Training, and Support Systems Foreign influence on the regular armed forces has historically been massive, vital, and controversial. Around the turn of the century, before Reza Shah unified the military, officers from Sweden, Britain, and Russia commanded various Iranian units. These officers were unpopular because they were perceived as occupiers rather than as advisers, and the seeds of xenophobia were planted. Aware of these sentiments, Reza Shah tried to minimize direct foreign military influence, although an exception was made for Swedish officers serving with the Gendarmerie. Between the two world wars, a large number of Iranian officers attended military academies in France and Germany, where they received command and technical training. In a further effort to counter the influence of both Britain and Russia (by that time, the Soviet Union) in Iranian affairs, Reza Shah attempted to establish closer ties with Germany, a relationship that would be controversial during World War II. After 1945 the United States gradually became more influential and had a significant impact on the Pahlavi dynasty's leadership and the military. With the establishment during World War II of a small United States military mission to the Gendarmerie (known as GENMISH) in 1943, Washington initiated a modest military advisory program. In 1947 the United States and Tehran reached a more comprehensive agreement that established the United States Army Mission Headquarters (ARMISH). Its purpose was to provide the Ministry of War and the Iranian army with advisory and technical assistance to enhance their efficiency. As a result, the first Iranian officers began training in the United States, and they were followed by many more over the next three decades. The United States initiated its military assistance grant program to Iran in 1950 (the bilateral defense agreement between Iran and the United States was not concluded until 1959) and established a Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to administer the program. In 1962 the two missions were consolidated into a single military organization, ARMISH-MAAG, which remained active in Iran until the Islamic revolutionary regime came to power in 1979. Between 1973 and 1979, the United States also provided military support in the form of technical assistance field teams (TAFTs), through which civilian experts instructed Iranians on specific equipment on a short-term basis. Although the GENMISH program ended in 1973, United States military assistance to Iran rose rapidly in the six years before the Revolution. United States military assistance to Iran between 1947 and 1969 exceeded US$1.4 billion, mostly in the form of grant aid before 1965 and of Foreign Military Sales credits during the late 1960s. The financial assistance programs were terminated after 1969, when it was determined that Iran, by then an important oil exporter, could assume its own military costs. Thereafter, Iran paid cash for its arms purchases and covered the expenses of United States military personnel serving in the ARMISH-MAAG and TAFT programs. Even so, in terms of personnel the United States military mission in Iran in 1978 was the largest in the world. Department of Defense personnel in Iran totaled over 1,500 in 1978, admittedly a small number compared with the 45,000 United States citizens, mostly military and civilian technicians and their dependents, living in Iran. Almost all of these individuals were evacuated by early 1979 as the ARMISH-MAAG program came to an abrupt end. Ended also was the International Military Education and Training (IMET) Program, under which over 11,000 Iranian military personnel had received specialized instruction in the United States. Washington broke its diplomatic ties with Tehran in April 1980, closing an important chapter with a former CENTO ally whose security it had guaranteed since 1959. The relationship had evolved dramatically from the early 1950s, when Iran depended on the United States for security assistance, to the mid-1970s, when the government-to-government Foreign Military Sales program dominated other issues. Arms transfers increased significantly after the 1974 oil price rise, accelerating at a dizzying pace until 1979. From fiscal year (FY) 1950 through FY 1979, United States arms sales to Iran totaled approximately US$11.2 billion, of which US$10.7 billion were actually delivered. The transfer of such large volumes of arms and the presence of thousands of United States advisers had an unmistakable influence on the Iranian armed forces. The preponderance of American weapons led to a dependence on the United States for support systems and for spare parts. Technical advisers were indispensable for weapons operations and maintenance. After the Revolution, Iranians continued to buy arms from the United States using Israeli, European, and Latin American intermediaries to place orders, despite the official United States embargo. Israeli sales, for example, were recorded as early as 1979. On several occasions, attempted arms sales to Iran have been thwarted by law enforcement operations or broker-initiated leaks. One operation set up by the United States Department of Justice foiled the shipment of more than US$2 billion of United States weapons to Iran from Israel and other foreign countries. The matériel included 18 F-4 fighter-bombers, 46 Skyhawk fighter-bombers, and nearly 4,000 missiles. But while the Department of Justice was attempting to prevent arms sales to Iran, senior officials in the administration of President Ronald Reagan admitted that 2,008 TOW missiles and 235 parts kits for Hawk missiles had been sent to Iran via Israel. These were intended to be an incentive for the release of American hostages held by pro-Iranian militiamen in Lebanon. Unverified reports in 1987 indicated that Iranian officials claimed that throughout 1986 the Reagan administration had sold Iran ammunition and parts for F- 4s, F-5s, and F-14s. In addition, Tehran reportedly purchased United States-made equipment from international arms dealers and captured United States weapons from Vietnam. Despite official denials, it is believed that Israel has been a supplier of weapons and spare parts for Iran's American-made arsenal. Reports indicate that an initial order for 250 retread tires for F-4 Phantom jets was delivered in 1979 for about US$27 million. Since that time, unverified reports have alleged that Israel agreed to sell Iran Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, radar equipment, mortar and machinegun ammunition, field telephones, M-60 tank engines and artillery shells, and spare parts for C-130 transport planes. By 1986 Iran's largest arms suppliers were reportedly China and North Korea. China, for example, is believed to have supplied Iran with military equipment in sales funneled through North Korea. According to an unconfirmed report in the Washington Post, one particular deal in the spring of 1983 netted Beijing close to US$1.3 billion for fighters, T-59 tanks, 130mm artillery, and light arms. China also delivered a number of Silkworm HY-2 surface-to-surface missiles, presumably for use in defending the Strait of Hormuz. As of early 1987, China denied all reported sales, possibly to enhance its diminishing position in the Arab world. North Korea agreed to sell arms and medical supplies to Iran as early as the summer of 1980. Using military cargo versions of the Boeing 747, Tehran ferried ammunition, medical supplies, and other equipment that it purchased from the North Korean government. According to unverified estimates, total sales by 1986 may have reached US$3 billion. Other countries directly or indirectly involved over the years in supplying

weapons to Iran have included Syria (transferring some Soviet-made weapons),

France,

Italy, Libya (Scud missiles), Brazil, Algeria, Switzerland, Argentina,

and the Soviet Union. Direct foreign influence, however, was minimal because

most purchases

were arranged in international arms markets. Moreover, the influence

of the major arms suppliers was balanced by other international relationships.

Many of the

above-mentioned West European states in 1988 had arms embargoes against

shipments to Iran, but nevertheless some matériel slipped through.

Also, West

European states often wished to keep communication channels open, no

matter how difficult political relations might have become. For example,

despite strong

protests from the United States, the British government in 1985 transferred

to Iran a fleet-refueling ship and two landing ships without their armament.

The British

also allowed the repair of two Iranian BH-7 Hovercraft. In 1982 Tehran

began negotiations with Bonn for the sale of submarines. Iran also approached

the

Netherlands and, in 1985, purchased two landing craft, each sixty-five

meters long and having a capacity exceeding 1,000 tons. The influence of

the Asian arms-

supplying countries was further minimized because purchases were made

in cash upon delivery with no strings attached. Finally, foreign influence

was less

pronounced in 1987 than at any time since 1925 because a defiant Tehran

espoused "independent" foreign and military policies, based on a strong

sense of Islamic

Domestic Arms Production In 1963 Iran placed all military factories under the Military Industries Organization (MIO) of the Ministry of War. Over the next fifteen years, military plants produced small arms ammunition, batteries, tires, copper products, explosives, and mortar rounds and fuses. They also produced rifles and machine guns under West German license. In addition, helicopters, jeeps, trucks, and trailers were assembled from imported kits. Iran was on its way to manufacturing rocket launchers, rockets, gun barrels, and grenades, when the Revolution halted all military activities. The MIO, plagued by the upheavals of the time, was unable to operate without foreign specialists and technicians; by 1981 it had lost much of its management ability and control over its industrial facilities. The outbreak of hostilities with Iraq and the Western arms embargo served as catalysts for reorganizing, reinvigorating, and expanding defense industries. In late 1981, the revolutionary government brought together the country's military industrial units and placed them under the Defense Industries Organization (DIO), which would supervise production activities. In 1987 the DIO was governed by a mixed civilian-military board of directors and a managing director responsible for the actual management and planning activities. Although the DIO director was accountable to the deputy minister of defense for logistics, Iran's president, in his capacity as the chairman of the SDC, had ultimate responsibility for all DIO operations. By 1986 a large number of infantry rifles, machine guns, and mortars and some small-arms ammunition were being manufactured locally. On several occasions, clerics delivering their Friday sermons in Tehran claimed that Iran was engaged in a full-scale military production program, and the Iranian press regularly reported the successful production of new items ranging from washers to helicopter fuselage parts. For example, the professional military displayed, at the Permanent Industrial Exhibition in Tehran, a collection of hermetic sealing cylinders for Chieftain tanks and artillery flame-deflectors with artillery pads. They also displayed Katyusha gauges, personnel carrier shafts, gears, gun pulleys, carriages for 50mm caliber guns, 155mm shells, bases for night-vision telescopic rifles, parts for G-3 rifles, various firing pins, and flash suppressors for 130mm guns. In 1987 the military took pride in being able to repair various transmitters, receivers, and helicopter engines. A number of unverified reports also alluded to the repair of the testing equipment of F-14 hydraulic pressure transmitters and generators. Similarly, Iran claimed to have manufactured an undisclosed number of Oghab rockets, probably patterned on the Soviet-made Scud-B surface-to-surface missiles the Iranians received from Libya. In mid-1984 the navy claimed to have successfully repaired the gas turbines of several vessels in Bandar-e Abbas. Moreover, Pasdaran units reportedly repaired Soviet- and Polish-made T-54, T-55, T-62, and T-72 tanks, captured from the Iraqis in 1982, at their armor repair center. The monopoly of the regular armed forces over domestic arms production

and repair industries ended in 1983 when the SDC authorized the Pasdaran

to establish

its own military industries. This new policy was in line with the Pasdaran's

growing political and military weight. Beginning in 1984, the first Pasdaran

armaments

factory manufactured 120mm mortars, antipersonnel grenades, various

antichemical-warfare equipment, antitank rockets, and rocket-propelled

grenades.

SPECIAL AND IRREGULAR ARMED FORCES

Troops of the Pasdaran in Qasr-e Shirin A primacy of state interest over revolutionary ideology was reflected in the Khomeini regime's treatment of the military. Reports to the contrary notwithstanding, the Khomeini regime never eliminated imperial Iran's regular armed forces. Certainly, key military personnel identified with the deposed shah were arrested, tried, and executed. But the purges were limited to high-profile military and political figures and had a clear purpose: to eliminate Pahlavi loyalists. As a means of countering the threat posed by either the leftist guerrillas or the officers suspected of continued loyalty to the shah, however, Khomeini created the Pasdaran, designated as the guardians of the Revolution. The Constitution of the new republic entrusts the defense of Iran's territorial integrity and political independence to the military, while it gives the Pasdaran the responsibility of preserving the Revolution itself. Days after Khomeini's return to Tehran, the Bazargan interim administration established the Pasdaran under a decree issued by Khomeini on May 5, 1979. The Pasdaran was intended to protect the Revolution and to assist the ruling clerics in the day-to-day enforcement of the new government's Islamic codes and morality. There were other, perhaps more important, reasons for establishing the Pasdaran. The Revolution needed to rely on a force of its own rather than borrowing the previous regime's tainted units. As one of the first revolutionary institutions, the Pasdaran helped legitimize the Revolution and gave the new regime an armed basis of support. Moreover, the establishment of the Pasdaran served notice to both the population and the regular armed forces that the Khomeini regime was quickly developing its own enforcement body. Thus, the Pasdaran, along with its political counterpart, Crusade for Reconstruction, brought a new order to Iran. In time, the Pasdaran would rival the police and the judiciary in terms of its functions. It would even challenge the performance of the regular armed forces on the battlefield. Since 1979 the Pasdaran has undergone fundamental changes in

mission and function. Some of these changes reflected the control

of the IRP (until its abolition in 1987) over both the Pasdaran and

the Crusade for Reconstruction. Others reflected the IRP's

exclusive reliance on the Pasdaran to carry out certain sensitive

missions. Still others reflected personal ambitions of Pasdaran

leaders. The Pasdaran, with its own separate ministry, has evolved

into one of the most powerful organizations in Iran. Not only did

it function as an intelligence organization, both within and

outside the country, but it also exerted considerable influence on

government policies. In addition to its initial political strength,

in the course of several years the Pasdaran also became a powerful