An Introduction to Persian Music

By: Hormoz Farhat

Catalogue of the Festival of Oriental Music,

University of Durham, UK

Tavoos Art Magazine - March 2008

The artistic gift of the Persian people has produced a staggering literary heritage, an exquisite tradition of decorative arts and handicrafts, a superb legacy in architecture, and a refined musical culture whose influence is evidence as far away as Spain and Japan.

Historic Retrospective The history of musical development in Iran [Persia] dates back to the prehistoric era. The great legendary king, Jamshid, is credited with the "invention" of music. Fragmentary documents from various periods of the country's history establish that the ancient Persians possessed an elaborate musical culture. The Sassanian period (A.D. 226-651), in particular, has left us ample evidence pointing to the existence of a lively musical life in Persia. The names of some important musicians such as Barbod, Nakissa and Ramtin, and titles of some of their works have survived. With the advent of Islam in the 7th century A.D., Persian music, as well as other Persian cultural traints, became the main formative element in what has, ever since, been known as "Islamic civilization". Persian musicians and musicologists overwhelmingly dominated the musical life of the Eastern Moslem Empire. Farabi (d. 950), Ebne Sina (d. 1037), Razi (d. 1209), Ormavi (d. 1294), Shirazi (d. 1310), and Maraqi (d. 1432) are but a few among the array of outstanding Persian musical scholars in the early Islamic period.

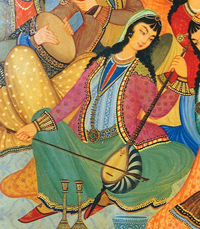

In the 16th century, a new "golden age" of Persian civilization dawned under the rule of the Safavid dynasty (1499-1746). However, from that time until the third decade of the 20th century Persian music became gradually relegated to a mere decorative and interpretive art, where neither creative growth, nor scholarly research found much room to flourish. Since the early 20's, once again, Persian music began to find broader dimensions. An urge to create rather than merely perpetuate the known tradition, and an interest to investigate the structural elements, has emerged. Fundamentally, however, what can be still recognized as the national music of Iran [Persia] is the tradition of the past with marked imprints of 19th century performance practices.

This traditional or classical music represents a highly ornate and sophisticated art whose protagonists are professional city musicians. Prior to the present century, such musicians were patronized by the nobility. Today, in a progressively modernizing society, they are generally engaged by broad casting and television media. They are also active as teachers both privately and at the various scholars and conservatories of music.

Structures

Perpetuated through an oral tradition, the classical repertoire encompasses a body of ancient pieces collectively known as the "radif" of Persian music.

These pieces are organized into twelve groupings, seven of which are known as basic modal structures and are called the seven "dastgah" (systems). They are : Shur, Homayun, Segah, Chahargah, Mahur, Rast-Panjgah, and Nava. The remaining five are commonly accepted as secondary or derivative dastgahs. Four of them: Abuata, Dashti, Bayat-e Tork and Afshari are considered to be derivatives of Shur; and , Bayat-e Esfahan is regarded to be a sub-dastgah of Homayun. The individual pieces in each of the twelve groupings are generally called "gushe", but each gushe has a specific and often descriptive title. A gushe is not a clearly defined musical composition; rather, it represents modal, melodic, and occasionally rhythmic skeletal formulae upon which the performer is expected to improvise. Thus, the radif submits an infinite source of musical expression. The flexibility of the basic material and the extent of the improvisatory freedom is such that a piece played twice by the same performer, at the same sitting, will be different in melodic composition, form, duration and emotional impact. The principle involved in the construction of Persian modes is based on the concept of conjunct and disjunct tetrachords comparable to the ancient Greek system. Chromaticism is not used and an octave never contains more or less than seven principal tones. Contrary to a persistent popular notion no such a thing as a quartertone exists in Persian [Iranian] music. A very characteristic interval, however, is the neutral, second. This is a highly flexible interval; but, in all its variations, it is noticeably larger than the minor second (half-step) and smaller than the major second (whole-step). Another interval peculiar to some of the modes is an interval which is larger than the major second, but not sufficiently large to be an augmented second. In authentic Persian music the western augmented second is not used.

Rhythmically, the majority of gushes are flexible and free and cannot be assigned to a stable metric order. However, in every dastgah, there are a number of metrically regulated gushes which are played among the free meter pieces in order to provide periodic variety in rhythmic effects. Both, double and triple meters are common; asymmetric meters, found in the folk music of certain regions, are rare in the classical music. As in the case of many non-western musical cultures, Persian music has not evolved a systematic harmonic practice. The development of this music has been primarily melodic. As such it has attained a far greater measure of melodic refinement and subtlety western music.

Instruments The musical instruments which have been known in the long history of Iran (Persia) are too numerous to name here. The following are those instruments, which are widely used at the present time:

Tar: A plucked string instrument with six strings and a range of two octaves and and fifth. Setar: An instrument related to the tar with the same range, but with four strings. The setar is strummed by the nail of the right index finger. Ud: The Arabian name for the ancient Persian instrument called barbat. It is also a plucked string instrument with nine to eleven strings. The European lute is a derivative of the ud. Kamancheh: A bowed instrument with four strings, played in the fashion of the violoncello, but with a size and tone range comparable to the violin.

Santur: A dulcimer played with delicate wooden mallets, with a range exceeding three octaves. Nay: Generic name for numerous verities of flutes. Tombak: The principal percussion instrument in the [Persian] classical music. It is vase shaped drum open on the narrow and end covered with a tightly stretched skin on the other side.

Dayere: Tambourine.

Folk and Popular Music The modal concepts in Persian folk music are directly linked with that of the classical music. However, improvisation plays a minor role as folk tunes are characterized by relatively clear-cut melodic and rhythmic properties. The function of each folk melody determines its mood. The varying aesthetic requirements of wedding songs, lullabies, love songs, harvest songs, dance pieces, etc., are met with transparent and appropriate simplicity. The majority of the classical instruments are too elaborate and difficult for the folk musicians. Instead, there are literally dozens of musical instruments of various sorts found among the rural people. In fact, each region of the country can boast instruments peculiar to itself. Three types of instruments, however, are common to all parts of the country. They are, a kind of shawm called surnay (or zorna), the various types of nay (flute), and the dohol, a doubleheader drum. A discussion of Persian music must necessarily include the new hybrid of mixed Persian-Western music which is functioning as a popular-commercial music. The use of western popular rhythms, an elementary harmonic superimposition, and relatively large ensembles composed of mostly western instruments, characterize this music. The melodic and modal aspects of these

compositions maintain basically Persian elements. On the whole, it would be something of an understatement to say that the artistic merit of such a melange as this is rather questionable.

Related Links

Related Links

Iranian Music

Iranian Music

Back to top

Back to top

Front Page

Front Page